Codebreak Newsletter #1: The Making of a Titan

How John D. Rockefeller's Chaotic Childhood Forged the World's First Business Empire

Throughout history, men and women have applied the perfect personal traits to a specific set of conditions, and as a result, built the greatest businesses—or business failures—in history.

As I began a long project to study the traits that made these people great, it didn't take long to realize that many of these traits repeated from individual to individual. So many, that I realized there are a finite set of human traits—things like risk tolerance, perseverance, ruthlessness—that exist in the universe of mankind.

Circumstances are not quite so finite as one couldn't have created a list all possible circumstances in the year 2000 that would have included the threats and opportunities related to a terrorist attack on 9/11, a Great Recession in 2008-2009, a Trump presidency (or two) and so on. However, even unique circumstances, like 9/11, have parallels throughout history. Pearl Harbor, for example, was equally unexpected, equally devastating, and even more impactful on the history of mankind.

If we can get our hands around these two things—finite traits and similar circumstances—then not only can we understand exactly how a titan of business achieved that status, but also how anyone could borrow the specific traits when they face similar circumstances.

Your New Advisory Board?

When you come to a crossroads that demands a decision of enormous import, why not take a quick check on how Bezos or Gates or Rockefeller and others would act in your exact situation? That's one hell of a parlor game, and potentially a very valuable one.

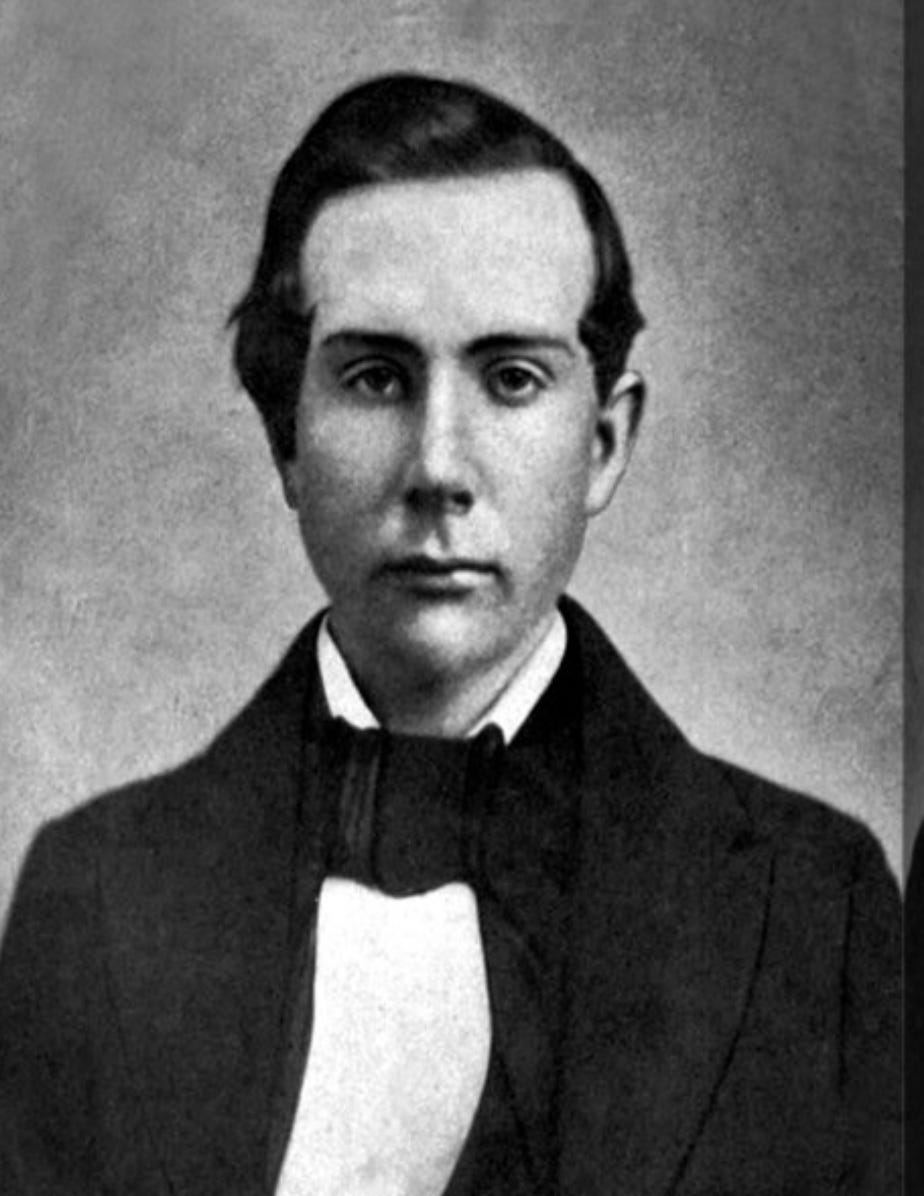

This four-part series dissects John D. Rockefeller—not as a historical curiosity, but as a strategic blueprint. His methods, both brilliant and brutal, remain as relevant today as they were 150 years ago. The goal isn't to worship the man, but to steal what worked.

Born Into Chaos: The Crucible of Control

Rockefeller's birth in 1839 came at a time marked by populist politics, territorial expansion, and the raw, unregulated rise of capitalism. The Industrial Revolution was taking hold, especially in Britain, and beginning to gain traction in the northeastern U.S. It was a world of canals, railroads, steam power, and rapid urbanization. A lot of dirt, a lot of noise, and the smell of potential fortunes to be made. The telegraph had not yet been invented.

In commerce, laissez-faire capitalism reigned. There were no antitrust laws, no income taxes, no meaningful regulations. Anyone with hustle and capital could rise—or crash. It was the age of merchant princes, land speculation, and frequent financial panics, including the Panic of 1837, a major depression that lingered through Rockefeller's early childhood.

In short, Rockefeller was born into a raw, wide-open economy with few rules, enormous opportunity, and high risk. It was a world where fortunes could be made from oil, steel, land, railroads—or snake oil. And from a boyhood home defined by duality—fraud and faith—he learned exactly how to navigate it.

A Con Man Father

Rockefeller’s father, William "Big Bill" Rockefeller, was a towering man with a booming laugh and slippery eyes, always coming and going with a carpetbag full of "cures" and half-truths. He called himself a traveling doctor, a businessman, and sometimes even a botanist, depending on who was listening. He sold potions out of the back of a wagon and charmed coins from the desperate with the same ease he used to charm women.

Home for Big Bill’s family was a house at the edge of the woods in upstate New York, a clapboard structure with peeling paint and too many occupants. Inside, the air was a stale mix of woodsmoke and lye soap. It was left to Big Bill's son, John D. Rockefeller, to make sense of a father who disappeared without notice for months at a time, and when he was home, kept two women—his wife and his mistress—in the crowded house for his pleasure.

The thin walls between the four rooms might as well have been bed sheets. As John lay on a straw mattress in the corner of a shared bedroom, he could hear the familiar rhythm of footsteps and murmuring voices as the women were summoned by Bill to his bed. Sometimes, it was his mother's voice. Sometimes, it was the other one—Lucy's. The voices were low, but the tension was high enough to make the air feel charged.

Bill managed to keep one or the other of his women pregnant most of the time, literally producing four children in two years. John, then, spent much of his youth in a small house with five women—his mother, Big Bill's mistress, and three sisters, two of whom were half-sisters by the mistress.

The Con Man or the Rock

The only stable influence in the house (a veritable rock) was John's Mother, Eliza Davison Rockefeller. She bore it all with a rigid spine and a Bible always at the ready. Pious, quiet, and strong, she raised the children on parables and discipline. She kept the accounts tidy, the meals modest, and the prayers consistent. Her husband's shameful arrangement was something she endured, not discussed.

A devout Baptist who prized discipline, thrift, and moral rectitude, Eliza maintained order in the household and taught her children to work hard, save money, and fear God.

She often reminded them that "willful waste makes woeful want."

From this clash of lives—chaos and order, indulgence and temperance—John forged the core traits that would define him as a businessman. He would impose upon himself, the traits of his mother, and come to abhor those of his father:

Discipline: While Big Bill lived day-to-day, John became obsessed with planning, record-keeping, and slow, deliberate moves. He balanced books for fun as a teenager and tracked every cent he earned. Big Bill lived day to day, while little John planned for a lifetime.

Control: Where his father let desire drive decisions, John became the master of self-restraint. Emotion never guided his hand in business; logic and order did.

Moral clarity (of a kind): Eliza's Baptist values didn't just influence John's piety—they embedded in him a black-and-white view of the world. He believed in purpose. He believed in reward through righteousness. Even as he built a monopoly others would describe as ruthless, he never saw himself as a villain. In his eyes, he was creating order out of disorder—just like his mother had.

He even believed from a very early age that God had ordained that he become rich so that he could give much of his wealth away...which he did.

The Teenager in a Suit

John D. Rockefeller landed his first real job—as an assistant bookkeeper at Hewitt & Tuttle, a small produce commission firm in Cleveland—when he was only sixteen years old. The year was 1855, and the country was on the cusp of industrial transformation. The teenager dressed each morning in a dark suit and tie, carried himself with the gravity of a man twice his age, and walked to work determined to make himself indispensable.

The firm paid him fifty cents a day, but the real value came from what he absorbed: the rhythms of commerce, the importance of detail, and, perhaps most crucially, the power of calm in a chaotic marketplace. He kept the books to the penny, tracked the flow of shipments, tallied receivables, and watched as fortunes were made—or lost—on the margins of price, timing, and trust.

Rockefeller quickly understood that information was leverage. The owners of the firm trusted him to keep meticulous records, and he saw how good bookkeeping wasn't just about math; it was about discipline, reliability, and revealing the hidden structure beneath apparent disorder.

It was the first place he saw clearly that the real power in business wasn't always in the product—but in the process.

He also developed a near-religious respect for cost control. At Hewitt & Tuttle, small mistakes meant lost profit, and lost profit meant reputations on the line. Watching this, Rockefeller adopted what would become a lifelong mantra: waste nothing. Every cent counted. Every decision had to pencil out.

In that first job, Rockefeller quietly formed the principles that would later dominate entire industries.

He wasn't yet the oil magnate or the feared monopolist—but the DNA was there: calm amid risk, an obsession with detail, and a belief that the game of business was won not by bold moves alone but by relentless, almost holy, precision.

The Leap to Ownership

At age 20, just as the Civil War was about to break out, Rockefeller partnered with Maurice B. Clark to create Clark & Rockefeller, a commodity brokerage dealing in grains, meats, and other goods. This was a small firm, but it marked the moment Rockefeller crossed the line from employee to owner. His real contribution wasn't the $1,000 he managed to invest in the firm, but the way he approached risk—minimizing it, studying every detail of logistics and cost, and seeking reliability where others chased speculation.

Rockefeller was not the type to take wild swings. He wanted control over his fate, and ownership was the path to that. He hated waste, inefficiency, and dependency on others. His leading business traits at the time were:

Moral Rectitude: Influenced by his devout Baptist mother, he viewed business as a moral activity. Profit was a form of divine favor for doing things the "right" way. That belief gave him psychological certainty others lacked.

Relentless Order: As a bookkeeper, he learned to obsess over the numbers. When he became a partner, he simply applied that obsession to bigger numbers and more moving parts.

To Rockefeller, business success came down to who could master the details without getting emotional.

Rockefeller's experience in the commodities business trained him in cost control, supply chain management, and disciplined negotiation—skills that would soon transfer seamlessly to the chaotic early oil industry. In the grain and meat trade, margins were tight, competition was fierce, and success depended on knowing not just prices, but freight rates, warehousing costs, and credit terms. Rockefeller mastered this. He learned to scrutinize every transaction, cut unnecessary steps, and forge relationships with railroads and shippers that gave him quiet leverage.

When he turned his attention to the burgeoning oil industry, he brought that same mindset to a far more volatile and immature market. While others speculated wildly on crude prices, Rockefeller focused on refining efficiency, transportation deals, and vertical control of the entire value chain—the boring, steady work of making pennies on the dollar, over and over. In effect, he treated oil like a commodity business that just happened to be disorganized, and he made it organized on his terms.

(Note: In several places, it's impossible not to see a direct comparison of Rockefeller and Gates. Both seemed to know more than others about the nuances of their chosen industry, and both chose to tackle a growing industry not through competing directly, but by identifying and controlling choke points in the value chain. Gates was thought to be in the "computer" industry, but chose the operating system chokepoint where those in that industry had to go through him and pay him a small toll, millions of times over. Rockefeller was in the "oil" industry, but avoided the dirty, dangerous task of drilling for oil, and sought control of the choke points of refining, transportation and distribution. One could hit the biggest gusher in the world, or sell the most personal computers, but they couldn't get it to consuers without going through Rockefeller or Gates. Codebreak will begin covering Bill Gates in about a month.)

Cloaked Ruthlessness

Even in these early years, hints emerged that Rockefeller possessed a cold willingness to dominate quietly, to cut others out, and to endure being disliked if it meant control. As a bookkeeper and then as a partner, he already showed signs of calculated ruthlessness, cloaked in politeness and moral calm.

He negotiated hard—even with friends—and had no problem using information asymmetry to his advantage. He kept immaculate records not just to be organized, but to know exactly where leverage lay. When suppliers or partners failed to deliver on terms, he remembered. He forgave nothing, though he almost never raised his voice. In disputes, he projected a kind of moral superiority that unnerved competitors—it was hard to pin him down, but easy to feel outmaneuvered.

Even as a junior partner, he quietly worked to push the senior partner, Maurice Clark, out of their firm when their visions diverged. By 1865, he orchestrated the buyout of Clark's share through a sealed-bid auction. The lower bidder would be obligated to sell at the price submitted by the higher bidder. Using information to his advantage, Rockefeller submitted a bid comfortably above what he knew would be Clark’s highest bid. He was right, and took control of the entire company.

It was bloodless, but unmistakably predatory. That event—the first real "kill"—revealed the inner steel: Rockefeller would smile, pray, and then take what he believed should be his.

Strategic Frameworks

Each week, Codebreak will tie the actions of a Titan to the strategic planning frameworks they used, whether or not they were aware of it at the time. Rockefeller's early years reveal several strategic frameworks that modern business leaders (including you!) can adapt for their own ventures:

1. Value Chain Analysis & Control through Vertical Integration. Whether or not he used the terms, Rockefeller instinctively analyzed every step in the relevant value chain from raw materials to the end customer. His obsession with freight rates, warehousing costs, and credit terms taught him to identify bottlenecks and inefficiencies others missed.

Modern application: Map your industry's value chain and look for the unsexy but critical steps where you can gain disproportionate leverage.

2. Information as Competitive Advantage. His meticulous record-keeping wasn't just organization—it was intelligence gathering. He knew his costs, margins, and supplier relationships better than anyone.

Modern application: Build superior data systems early. The company with the best information usually wins the negotiation. And for goodness sake…learn some accounting! It’s the only thing Warren Buffet tells young people they simply must understand for any role in the business world!

3. Switching Costs Strategy By making himself indispensable to suppliers and customers through superior reliability and cost management, Rockefeller created switching costs before the concept existed.

Modern application: Focus on becoming so integral to your customers' operations that replacing you becomes costly and risky.

4. Cost Leadership Through Operational Excellence Rather than competing on product innovation, Rockefeller competed on operational efficiency—doing the same thing as competitors but cheaper, faster, and more reliably.

Modern application: Sometimes the best strategy isn't being different, or first, or highly innovative…but simply being dramatically better at the fundamentals.

5. Strategic Patience vs. Tactical Aggression Rockefeller waited years to make his move into oil, but when he acted—like buying out Clark—he moved decisively and completely.

Modern application: Plan slowly, execute quickly. Patient strategy combined with aggressive tactics is often unbeatable. Rockefeller consistently drove most of the risk out of a business venture that others would perceive as highly risk.

Coming Up…

Next week, we'll explore how Rockefeller applied his personal traits and these strategic principles to enter the oil industry and build his first devastating competitive advantages through refining and transportation monopolies.